"The Southern people, driven to the wall, have no remedy but that of political independence. Forbearance has not only ceased to be a virtue, but has become absolute cowardice."

Cockades of South Carolina, Palmetto fronds were worn by Charlestonians to symbolize their defiance of the Union at the secession convention in December of 1860. Later, the cockades were worn throughout the South as emblems of sectional solidarity.

DECEMBER 17,1860

Nothing could keep Edmund Ruffin away from the secession convention. Not his grief for his dear daughter Elizabeth, who had just died in childbirth. Not the heavy storm that had covered his plantation north of Richmond, Virginia, with nine inches of snow and was discommoding travelers in the region. Ruffin had long been agitating for Southern independence, and now that South Carolina was on the verge of quitting the United States, he was determined to be there, to witness with his own dimming eyes (he was 66) the dawn of the glorious new era. So on December 17, 1860, the old man packed his luggage, journeyed by carriage and river steamer to Richmond, and there caught a southbound train.

Ruffin's destination was the South Carolina capital, Columbia, where delegates from all over the state convened on the 17th declared purpose terminating relations with the government "known as the United States of America." But during a stop along the way at Wilmington, North Carolina, Ruffin learned that the convention had been driven out of Columbia by an outbreak of smallpox and had reconvened in Charleston-an appropriate move, since that city had always been a hotbed of secessionist sentiment. He changed trains accordingly and arrived in Charleston on the morning of December 19. He was lucky to find accommodation in a tiny, unheated room in the Charleston Hotel.

The town was overflowing with enthusiastic Southern patriots-Southrons they called themselves. In addition to the convention delegates, the entire South Carolina government was on hand, along with such visiting dignitaries as the Governor of Florida, official representatives of Alabama and Mississippi, four former United States senators and one former United States attorney general. Ruffin encountered scores of old friends and fellow "fire-eaters" who had been leaders in the fight to break up the Union. They were the gentry of the South: planters and newspaper publishers, judges and lawyers, clergymen and banker--some of them weaning the bright uniforms and the gold braid of officers in the militia. David F. Jamison, a gentleman-scholar who lived quite graciously on the proceeds of a 2,000-acre, 70-slave plantation, was the presiding officer of the convention, and he saw to it that Ruffin would have a seat in the two jam-packed convention buildings.

Using a gavel incised with the word "Secession," President Jamison called the session of December 19 to order in St. Andrew's Hall, a small auditorium where speakers could make themselves heard more easily than in the big auditorium of Institute Hall. The exact language of the Ordinance of Secession was still being mooted in committee, and Jamison pointedly read a telegram from the Governor of Alabama urging the convention to brook no delay.

Many things remained to be settled. Concurrent with secession, the state of South Carolina would cease to be bound by federal law, and a complete new code for the infant republic of South Carolina would have to be framed. Local patriots had to be appointed to take over the functions of United States officials. How best could the postal service be handled? What regulations would need to be adopted for collecting customs at the port of Charleston?

The delegates quickly addressed themselves to one matter that soon would become a critical problem. A committee was appointed to report on United States properties inside the territorial limits of South Carolina; most prominent of these were three federal military installations in Charleston Harbor Fort Moultrie, Castle Pinckney, and Fort Sumter. A resolution was then passed instructing the Committee on Foreign Relations to send three commissioners to Washington to negotiate with the United States government for the transfer of all such real estate to the new republic of South Carolina. Regarding this and other momentous issues, Edmund Ruffin made a laconic entry in his diary: "Heard several interesting discussions on subjects incidental and preliminary to the act of secession.

Everybody was disappointed when the day end~ without a formal declaration of secession. But during the delay, the symbols of rebellion-the colors and devices of South Carolina-had time to come into full bloom throughout Charleston. Assistant Surgeon Samuel Crawford, attached to the small federal garrison at Fort Moultrie, reported that "blue cockades and cockades of palmetto appeared in every hat; flags of all description, except the National colors, were everywhere displayed. The enthusiasm spread to more practical walks of trade, and the business streets were gay with bunting and flags, as the trades people, many of whom were Northern men, commended themselves to the popular clamor."

At noon the next day in St. Andrew's Hall, Ruffin attended a closed meeting of the Committee to Prepare an Ordinance of Secession. The product of the committeemen's anxious travail was read aloud:

We, the people of the State of South Carolina, in Convention assembled, do declare and ordain . . . that the union now subsisting between South Carolina and other States under the name of "The United of America" is hereby dissolved.

At 1:15 p.m. all 169 delegates voted to adopt the ordinance as read. The document was then turned over to the attorney general of South Carolina to see that it was properly engrossed. The public signing ceremony was scheduled to take place in Institute Hall at 7 o'clock that evening.

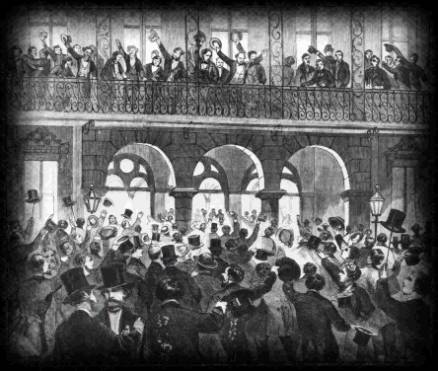

Separatists rallies in front of Charleston’s Mills House during the South Carolina secession crisis of December 1860. Impassioned Speakers on the hotel balcony kept Whipping up the crowd’s enthusiasm.

The delegates-the founding fathers of the new nation-emerged from the hall and were immediately greeted by the start of a long, loud, citywide celebration. Church bells were rung, cannon were fired and joy was nearly universal. One of the few people to admit dissatisfaction was a cranky old judge named James Louis Petigru. Petigru was walking down Broad Street when the bell ringing began and, upon bumping into a friend at the city hall, he inquired sourly of the man, "Where's the fire?" Petigrus friend replied that there was no fire, just happy noise to celebrate secession. "I tell you there is a fire," the judge retorted. "They have this day set a blazing torch to the temple of Constitutional liberty and, please God, we shall have no more peace forever." At 7 p.m., the delegates to the convention marched into Institute Hall through dense crowds of celebrants. The signing ceremony took too hours. Finally, President Jamison held up the completed document and declared, "I proclaim the State of Sc h Carolina an independent commonwealth." An enormous roar of approval shook 'e hall, the deed had been done.

The convention adjourned, and old Edmund Ruffin-honored with the gift of a pen that had signed the Ordinance of Secession-made his way back to the Charleston Hotel. Once he had reached his room, he took out his diary and contentedly summed up the hectic scene: "Military companies paraded, salutes were fired, and as night came on, bonfires, made of barrels of rosin, were lighted in the principal streets, rockets discharged and innumerable crackers discharged by the boys. As I now write, after 10 p.m., I hear the distant sound of rejoicing, with music of a military band, as if there were no thought of ceasing."

Exactly what had happened in Charleston on December 20, 1860? The answer was by no means certain at the time.

According to Northerners with a Constitutional turn of mind, nothing had happened; the United States was a sovereign ·nation, not a mere confederation of independent states; thus by its very nature the republic was indivisible, and secession was impossible Other, more pragmatic Northerners regarded secession as a very real crime against the Constitution, a breach of popular contract so grave that force of arms would have to put it right. Most Southerners, for their part, were willing to take up arms to defend their action. And many people on both sides saw secession as the only peaceful way out of their quarrels.

In any case, the first of the Southern states had seceded. It was the beginning of the end of the early Union-an event that Southerners called the second American Revolution Looked at another way, it marked the end the beginning-an abrupt halt to the nation's first phase of helter-skelter growth It. would lead, after four months of increasing tension and hostility, to the start of the deadliest of American wars, a four-year struggle that would consume the lives of more than 620,000 young Americans, or roughly one out of every 50 citizens.

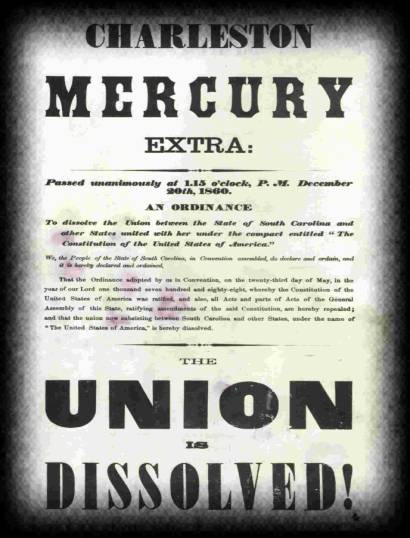

of the Charleston Mercury hails South Carolina’s Vote to secede. The extra hit the Streets at 1:30 p.m. on December 20, 1860, just 15 minutes after the Ordinance of Secession was passed.

That the nation was so vigorous made its breakup and descent into war all the more tragic. Europeans were beginning to recognize the United States as a world power and the epitome of democratic ideals. Indications of prosperity and progress were abundant:

Well-off families in large cities were beginning to have indoor privies; plans were in the works for a railroad to California; and a transatlantic cable-which had twice barely failed-seemed certain to succeed in the near future. Moreover, some gifted leaders had strode the political stage in recent decades-men who had fashioned careful compromises to resolve sectional disputes. But the plain fact of the matter was that the North and the South had become so different-so damnably incompatible and antagonistic-that no amount of political ingenuity could avail.

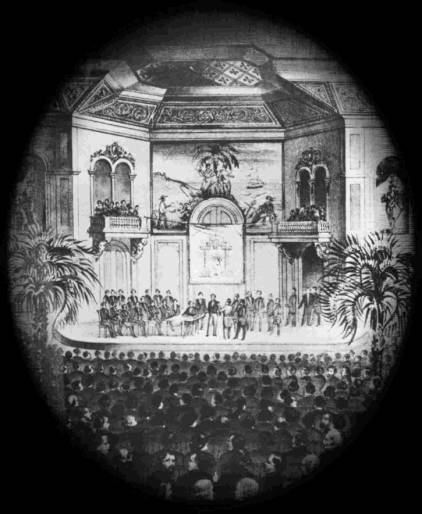

Secession Hall, witness the ceremonial signing Of the Ordinance of Secession On the night of December 20, 1860. “The signing occupied more than Two hours,” said one observer, “During which time there was nothing To entertain the spectators except Their enthusiasm and joy.”

The two sections had been following divergent paths ever since the start of settlement in America. Geography and climate at once began shaping radically different economic and social patterns in the North and in the South. In the upper Atlantic regions, the terrain was hilly and rocky, with the interior heavily forested and difficult of access. These conditions tended to keep farms small and to build up large pools of population along the coast; many Northern settlers became seamen, fishermen, shipbuilders and merchants. When the Industrial Revolution began late in the 18th Century, entrepreneurs moved steadily inland along the rivers, building mills and factories to exploit the ample waterpower. They were followed by plenty of surplus workers from the coastal cities. By the early years of the 19th Century, the North was becoming a region of large scale industry, big cities and long-distance commerce, with a great deal of small-scale farming of varied food crops.

In the South, the terrain and climate favored an agrarian way of life. Good land was plentiful and accessible, for the coastal plain extended well inland, and the rivers were navigable to the fall line far to the west. The warm weather, the long growing seasons and the great stretches of level, unbroken terrain were just right for the plantation system-a method of large-scale, intensive farming in which gangs of unskilled laborers worked to cultivate a single cash crop: tobacco or rice, sugar cane or long-staple cotton. The South's most important crop, short-staple cotton, became profitable in the 1790s, when Eli Whitney's cotton gin solved the problem of separating the tough seeds from the fleecy white fiber.

At first, workers were everywhere in short supply in the Southern colonies, with white indentured servants doing much of the menial labor. But the real plantation work forces were gradually provided by the slave trade with Africa and the West Indies. In the 17th Century, slavery was still widely regarded as a legitimate means of maintaining the subservience of conquered enemies or analphabetic inferiors. More than a century later, slaves were recognized as a form of property in the United States Constitution. Being mere chattel, the slaves were not citizens and had no vote. But in an effort to redress the imbalance of national representation between the thinly settled South and the populous North, the Southern states were allowed to count each slave as three fifths of a person for their Congressional apportionment. Thus an added indignity for slaves:

Votes conferred by the head count of blacks were cast by whites to keep the slaves servile.

As black slavery spread in the South during the 18th Century, opposition to it spread in the North. The first important protests came from austere Protestant groups, primarily the Quakers, who objected to the ownership of people on moral grounds. 0ther Northerners, however, considered such protests academic, for slavery was fading out in their states; manufacturers and businessmen preferred self-sufficient employees who could be hired and fired to suit economic conditions. Thus, since the Northern states did not need or want slaves, they outlawed slavery one by one.

There were enlightened Southern planters who agreed that slavery-they referred to it as "our peculiar domestic institution"-was distasteful. Some liberals among them began freeing their slaves. Other planters pointed out correctly that they were far more humane than their South American counterparts, who tended to work their slaves to death. Still, the Southern planters profited handsomely by whatever degree of humane treatment they practiced. By 1808, when the United States became the last democratic nation to ban international slave trade, Southern slaves were living long enough, and reproducing fast enough, to provide their masters with a lucrative sideline of salable human chattel.

It turned out that slavery and the plantation system were self-perpetuating. In a pattern set early in the tobacco plantations of Virginia, intensive one-crop farming quickly exhausted even the best of soils. The big planters, who lived like feudal lords on very small amounts of cash, declined to sacrifice profits by rotating crops, letting fields lay fallow, or fertilizing to any substantial degree. Instead, the planters purchased more and more land-and so they needed more and more slaves to work the new holdings. Latecomers established plantations farther to the west and south, practicing the same one-crop style of agriculture, usually with cotton. By the early 18th Century, the great Virginia families with plantations dotting the Tidewater were expanding inland, driving the South's small yeoman farmers ahead of them into less favorable lands in the piedmont areas and the Appalachians beyond. By the 1 820s, cotton culture was spreading rapidly southward into the Gulf Coast regions, and during the next decade it overleaped the Mississippi into Texas.

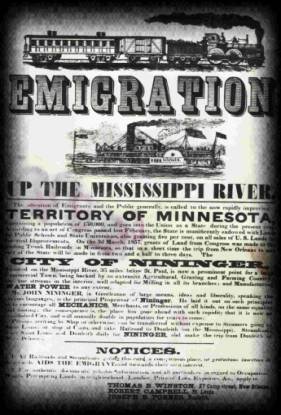

from 1857 urges land-Hungry immigrants to homestead In Minnesota Territory. Such Promotions worked. The heavy influx Of settlers, many of German origin, Swelled the population from 6,000 in 1850 to 150,000 by 1857, the year Before Minnesota became the 32nd State. Minnesota and other North Central states were firmly linked to The Northeast-and to the Union-By the prevailing pattern of trade.

Production of cotton rose steeply-from $15 million in 1810 to $63 million in 1840. The value of slaves also increased sharply, from $600 each in 1810 to $1,000 in 1840 to $1,200 and even $1,800 for a prime field hand on the eve of secession. But the lot of the planters did not improve. Lacking middlemen and credit arrangements of their own, planters were victimized by Northern factors, who would pay only the prices set by the English market. Planters suffered cruelly from the volatile American economy, with its quick succession of booms and busts, flush times and depressions.

From time to time, constructive Southerners attempted to diversify their economy-to industrialize, if only to the extent of building mills to process their own cotton. But the Southern planters, slave-poor and land-poor in their struggle to expand apace with demand, had very little to invest; the entire South could not muster as much capital as the single state of New York. Moreover, Southern efforts to raise Yankee capital for building mills and factories generally failed; Northern bankers and financiers were unwilling to invest in a region that lacked both a free labor supply and an adequate transportation system.

In the view of many Southerners, the South had become a hapless colonial region that was exploited by the industrialized North. "Financially we are more enslaved than our Negroes," complained an Alabamian. In 1851 a newspaper in Alabama published a long and bitter inventory of the ways in which the South was a vassal to the North: "We purchase all our luxuries and necessities from the North. Our slaves are clothed with Northern manufactured goods, have Northern hats and shoes, work with Northern hoes, plows and other implements. The slaveholder dresses in Northern goods, rides in a Northern saddle, sports his Northern carriage, reads Northern books. In Northern vessels his products are carried to market, his cotton is ginned with Northern gins, his sugar is crushed and preserved with Northern machinery, his rivers are navigated by Northern steamboats. His son is educated at a Northern college, his daughter receives the finishing polish at a Northern medical college, his schools are furnished with Northern teachers, and he is furnished with Northern inventions.

Against this backdrop of economic troubles, a succession of great political crises beset the nation in the first half of the 19th Century. All of them were brought to seemingly viable resolutions. But each one raised the level of sectional hostility to new heights, and each one left behind a legacy of deepening rancor and frustration. By the beginning of the decade of the 1850s, there was precious little left of the sense of common interest and mutual sympathy that had bound the North and the South together during the American Revolution.

It was the country's great good fortune in political leaders who represented different interests with power, clarity, honest conviction and unfailing responsibility. Daniel Webster of New Hampshire and later Massachusetts spoke for mercantile, antislavery New England. Henry Clay of Kentucky, representing both slave owners and a strong antislavery element in his border state, became the mediator for the nation. John C. Calhoun of South Carolina captured in his changing political outlook the course of the country and the trend of the times: He began his career as an ardent nationalist and ended it as a passionate sectionalist.

Lawyer Calhoun cut an impressive figure when he arrived in Washington in 1811 as a newly elected Congressman from South Carolina. At the age of 29 he was tall and square-shouldered, a man with the burning eyes of a visionary. His seriousness of purpose and his Calvinist piety allowed little room for humor; logic and law were what consumed his thoughts. He was said to have sent his wife-to-be a love poem consisting of 12 lines; each of which started with the word "Whereas"-except for the last, which began with "Therefore."

In his calm, crisp courtroom manner, Calhoun swayed men and won votes with his own particular brand of radical patriotism. Declaring that "the honor of a nation is its life," he successfully pushed for war against British aggression in 1812. Later he joined with Henry Clay to promote what came to be called the "American system," a master plan for national strength and growth that included proposals for national defense, a national protective import tariff, a national bank for a uniform currency and a nationwide transportation system.

Whose noncommittal attitude toward Slavery often prompted criticism, outraged abolitionists with his speech In favor of the 1850 Compromise Condoning slavery. Poet Ralph Waldo Emerson accused him of venality in aBitter couplet: “Why did all manly Gifts in Webster fail? / He wrote on Nature’s grandest brow, For Sale.”

Calhoun’s opponents, chiefly conservative New Englanders argued that the Constitution did not delegate such sweeping powers to the federal government, that the American system would usurp authority belonging to the individual states. But the notion of states' rights was anathema to young Calhoun. "We are under the most imperious obligation to counteract every tendency to disunion," he declared. "Let us, then, bind the Republic together with a perfect system of roads and canals. Let us conquer space." On February 13, 1819, the first of the period's great struggles was joined. James Tallmadge, an obscure one-term Representative from New York, introduced a resolution that electrified the United States Congress. The debate that it provoked came, the aging Thomas Jefferson wrote, "like a fire bell in the night," which "awakened me and filled me with terror. I considered it at once the knell of the union." To another former President, John Quincy Adams, it seemed to be "a title page to a great tragic volume."

Whose Compromise of 1850 reconciled North and South for a decade, Presented himself as a presidential Candidates five times and was five Times rebuffed. Out of his Disappointments came his famous Declaration that he “would rather be Right than be President.”

Tallmadge's measure sought to prohibit slavery in the Missouri Territory, a section of the Louisiana Purchase that was petitioning to enter the Union as a slave state. The proposed restriction reflected a growing antislavery sentiment on the part of Northern legislators and represented a challenge that the South could ill afford to ignore, for it had implications that extended far beyond the status of Missouri. It was cotton that produced the lion's share of the South's income, and planters were fearful that unless the cultivation of cotton continued to expand, their whole economy would wither and die as cultivated areas were exhausted. And, just as frightening to Southerners, it threatened to shift the balance of power in Washington in favor of the North.

Was so unyielding and so Passionate in his defense of Southern Rights that a visiting Englishman Called him both “the cast-iron man” And “a volcano in full force.”

Southerners had already lost control of the House of Representatives to the Northern states, whose populations were swelling as immigration increased. The Senate was controlled by neither section: Of 22 states in the nation in 1819, exactly half were free and half were slave. But if Missouri entered the Union as a free state, the Senatorial balance would tip against slavery. The South would then be helpless to prevent the passage of ruinous legislation: tariffs that crippled the Southern cotton trade with Europe; huge funds allocated to the development of ports, canals and turnpikes beneficial to the North; eventually, the abolition of slavery, even in the slave states.

The volatile issue of the extension of slavery to Missouri touched off an acrimonious debate that spanned two sessions of Congress. The Northerners were seething with moral outrage. "How long will the desire for wealth render us blind to the sin of holding both the bodies and souls of our fellow men in chains?" demanded Representative Arthur Livermore of New Hampshire. "Do not, for the sake of cotton and tobacco, let it be told to future ages that, while pretending to love liberty, we have purchased an extensive country to disgrace it with the foulest reproach to nations!"

The Southern planters, trapped in their dependence on slavery, accused Northerners of exaggerating the evils of the institution and challenged the right of the North to meddle in the affairs of the South. "The slaveholding states," declared the Lexington, Kentucky, Western Monitor, "will not brook an invasion of their rights. They will not be driven by compulsion to the emancipation, even gradually, of their states."

Not until 1820 was the debate over the admission of Missouri finally calmed by moderates. Henry Clay had stepped forward with a compromise that seemingly settled the slavery issue. To preserve the tenuous balance in the Senate, Missouri was to be admitted as a slave state and Maine would come into the Union as a free state. Further, a demarcation line would be drawn from east to west at latitude 360 30'. Henceforth, all new states that might be fashioned from Louisiana Purchase territories north of that line would be free, whereas all of those below it would be slave.

The Missouri Compromise papered over the problem of the extension of slavery, but it was satisfactory to no one. For the first time in the short history of the nation, an action by Congress had aligned the states against each other on a sectional basis. Suspicions grew on both sides. Northerners suspected that a Southern cabal they called "the Slave Power" was conspiring to circumvent the principle of rule by the majority. Southerners, in turn, suspected that Northerners were plotting to destroy them. Said James M. Garnett of Virginia, "It would seem as if all the devils incarnate, both in the Eastern and Northern states, are in league against us."

Calhoun did his best to allay Southern fears of a Northern conspiracy against slavery. But cries for help from the planter: of South Carolina were pulling him to their side. Tariffs that protected the profits of Northern manufacturers caused increasing hardship in the South, raising the prices that Southerners had to pay for imported manufactures. And then, in the 1820s, the Southern predicament was further exacerbated by a recession.

More and more Southerners, Calhoun included, turned against nationalism. In 1827, after his election as Vice President in the administration of John Quincy Adams, he made his first break with his past. On the Senate floor, with the vote tied on a new tariff bill, Calhoun cast the decisive ballot against it. But the next year, rival politicians managed to force through Congress another, higher tariff on a variety of manufactured goods. Angry Southerners labeled it the Tariff of Abominations, and soon they were blaming it for all their economic ills.

In Calhoun's South Carolina, those troubles were acute. As plantation profits declined during the recession, planters abandoned their fields. Roads and bridges fell into ruin. Calhoun wrote his brother-in-law in 1828 "Our staples hardly return the expense of cultivation, and land and Negroes have fallen to the lowest price and can scarcely be sold at the present depressed rates." A vocal group of South Carolina radicals went so far as to speak of secession as a means of eradicating the intolerable tax.

Calhoun now faced a dilemma. He had set his sights high; he wanted to succeed President Andrew Jackson. But to stand any chance he would have to tread a precarious path, satisfying the radicals at home, maintaining Jackson's friendship, and at the same time somehow moderating the angry reaction of the Northern businessmen who were in favor of protective tariffs. What he needed was a program.

In the summer of 1828, Calhoun secluded himself at Fort Hill, his plantation in Pendleton District, and pored over American state papers in search of a defense against the tariff. He paid particular attention to the 1781 Articles of Confederation, which recognized the "sovereignty, freedom, and independence" of each state, and to the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798 and 1799, which stated the controversial opinion that the Constitution was a "compact" between the states, each of which had the right to pass on the constitutionality of the federal government's acts. In the case of federal laws that were unfair or unfavorable to particular states, the Kentucky Resolution declared:

"It is the right and duty of the several states to nullify those acts, and to protect their citizens from their operations."

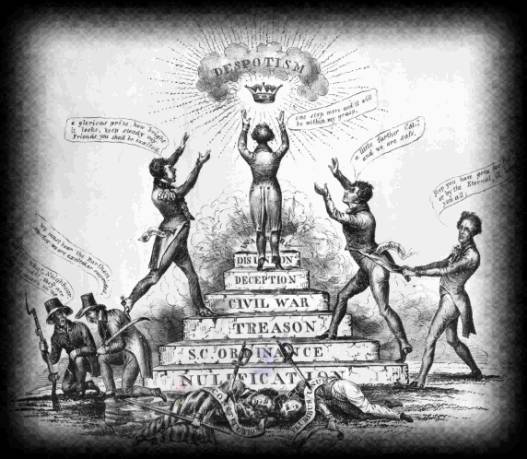

By summer's end, Calhoun had developed the doctrine of nullification, which he published in a pamphlet. In it, he proclaimed the right of any state to overrule or modify not only the tariff but also any federal law deemed unconstitutional. Nullification was a complete theory of government that placed the greatest powers on the state level rather than the national. With this proclamation of states' rights, Calhoun had come full circle in his political philosophy.

Calhoun's doctrine failed to produce the results he had anticipated. It alarmed the North and antagonized President Jackson, who saw nullification as a knife poised over the Union's vitals. Jackson made his sympathies clear with a toast at a gathering just after nullification was unveiled on the Senate floor. "Our Federal Union!" said Old Hickory. "It must and shall be preserved!" Calhoun, forced to hoist his own standard, could only respond: "The Federal Union-next to our liberty, the most dear."

The showdown over the nullification issue came in 1832, when a South Carolina convention formally disallowed two federal tariff acts. President Jackson labeled that action treasonous and immediately called South Carolina's bluff by threatening to use force to ensure obedience to the tariff law. Calhoun and his fellow nullifiers were unable to muster support from the other Southern states, and they finally accepted a compromise tariff of lower rates. Calhoun had learned a lesson-that it would take a group of states to make the doctrine of states' rights stick. He began at once to recruit followers and to spread the gospel of Southern solidarity.

Even as Calhoun campaigned for Southern unity, opposition to slavery came of age in the 1 830s, winning acceptance in a period of reform and religious revivalism. The various antislavery factions still adhered to different principles and goals, which prevented cooperation, not to mention consolidation. Nevertheless, all the groups were backed by a sympathetic press and separately made many converts in their furious efforts to rid the nation of slavery.

The most important antislavery factions were groups of abolitionists; they wanted slavery outlawed and the freed blacks absorbed into society on an equal footing with whites. Besides these social idealists, a group of political pragmatists plumped for abolition only in the new territories, thinking slavery would eventually perish in the Southern states. And there were numerous emancipationists. Like the abolitionists, they demanded that the slaves be freed. But they wanted no part of the freed slaves as fellow citizens; far better, they said, to ship all blacks to Africa. One emancipationist organization, the American Colonization Society, raised large sums of money to ship freed blacks to Liberia. An African nation was set up in 1847 to receive more freed slaves.

Of Southern affronts to the Union, Reaches for a despot’s crown in this Northern cartoon from 1833. At right President Andrew Jackson warns Calhoun and his fellow separatists to Reverse their perilous course.

Of all the antislavery groups, the abolitionists were the most vigorous and vociferous promoters of their cause. Angry and eloquent, they damned slavery as a sin and slave owners as criminals. The fiercest of them all was New Englander William Lloyd Garrison, founder of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator. Garrison insisted that opposition to slavery was more vital than the preservation of the Union, and because the Constitution protected slavery, he burned a copy in public, calling the document "a covenant with death and an agreement with hell." Garrison made no apology for his extreme views. "I do not wish to think or speak or write, with moderation," he raged. "I will be as harsh as truth, and as uncompromising as justice. And I will be heard."

Some abolitionists were so daring as to take their crusade into the camp of the enemy. James G. Birney, a wealthy man who had owned slaves himself, boldly attacked the institution in the slave state of Kentucky. So did emancipationist publisher Cassius M. Clay. Protected somewhat by his fearsome reputation as a duelist and by the two cannon that guarded his office, Clay railed against slavery in his Lexington newspaper. Finally, irate Kentuckians put him out of business by dismantling his press in his absence and shipping it to Cincinnati.

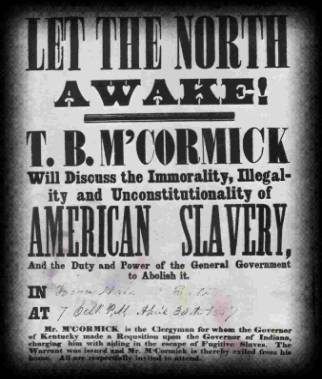

Given in Eaton, Ohio, by a clergyman Wanted in Kentucky for helping Runaway slaves. Many fugitive blacks Passed through Kentucky on their Way into Ohio and thence to Canada.

A few abolitionists risked their lives to help slaves flee north to freedom on the so-called Underground Railroad. The fugitives were smuggled in wagons and led through woods to the farmsteads and city houses of sympathizers; they followed many escape routes, most of them ending in Ohio and Indiana. Workers on the Railroad claimed to have rescued or assisted as many as 100,000 escapees in three decades-undoubtedly a considerable exaggeration, since the South reported only 1,000 escapes a year. Yet the Railroad was invaluable as an inspiration for those who opposed slavery as well as for those who plotted to escape it.

Naturally, the abolitionist campaign enraged the Southerners. And it also frightened them, conjuring the nightmarish possibility of an immense uprising among their more than two million slaves. A small version of such an insurrection occurred in the summer of 1831, when a Virginia slave by the name of Nat Turner led about 70 fellows on a bloody rampage that left 55whites dead. Turner and 16 of his followers were tried and quickly hanged, and soon afterward the slave states acted to prevent abolitionist rhetoric from sparking much worse disasters. Stiff laws were passed restricting freedom of speech and the press; abolitionist tracts were actually burned in the United States Post Office in Charleston.

Faced with increasing pressures both from without and from within, Southerners closed ranks. It ceased to be safe to whisper even a word against the "peculiar institution," and any stranger suspected of antislavery agitation was likely to be hustled out of town in a coat of tar and feathers. Those humane planters who once had thought of slavery as a temporary aberration now claimed defensively that the institution was a positive good, that it benefited the slave with food, clothing and housing, that it uplifted him with Christian tutelage.

In 1838 John Calhoun endorsed the new Southern attitude: "Many in the South once believed that slavery was a moral and political evil. That folly and delusion are gone. We see it now in its true light, and regard it as the most safe and stable basis for free institutions in the world."

A new political crisis threatened with the beginning of the Mexican War in 1846. Americans from every state rushed to join the Army and to fight in behalf of a jingoistic credo with a newly coined name, Manifest Destiny. The credo excused any and all conquest by declaring that it was the God-given right of Americans to inherit the continent from sea to sea. Although Manifest Destiny was popular nationwide, it was made to order for Southern interests. Some Southern firebrands openly discussed annexing Mexico once the government of Santa Anna surrendered. The country could be broken up into dozens of new slave states. The horizons of the more ardent cotton imperialists extended even to the Spanish colony of Cuba, where slavery conveniently existed. The acquisition of just a few new states for slavery would give the South control of the Senate, where the count presently stood at 15 slave states and 15 free states.

John Calhoun did not share the Southerners' enthusiasm for war with Mexico. He foresaw a bitter dispute over the enticing Mexican spoils, which he called "forbidden fruit." And he was right: Even before the brief conflict with Mexico came to an end, a move was made in Congress that sent Northerners and Southerners to their political ramparts for the third time in as many decades. The provocation came from David Wilmot, a slovenly, profane, tobacco-chewing country lawyer from Pennsylvania. He introduced a measure proposing, "neither slavery or involuntary servitude shall ever exist" in any territory that might be acquired as a result of the Mexican War. The Wilmot Proviso never made its way into law: Over a span of six months it passed the House twice, but it failed in the Senate. Nevertheless, its impact was staggering. It split Congress along sectional lines, with nearly all members voting on the measure not as Democrats or Whigs-the two major parties of the day-but as Northerners or Southerners. An unsuccessful Southern attempt to quash the proviso in the House demonstrated the extent of the rift: 74 Southerners and four Northerners voted to table Wilmot's measure, 91 Northerners and three Southerners voted to keep it alive. "As if by magic," a Boston journalist wrote of the proviso, "it brought to a head the great question which is about to divide the American people."

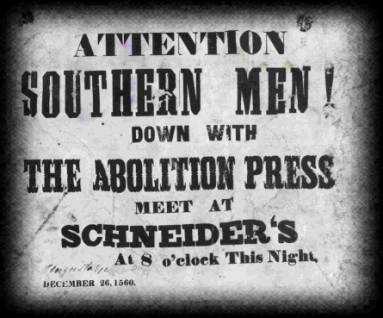

Produced with a misprinted date, Announces a rally in Augusta, Georgia, to protest the torrent of Antislavery tracts from the North. Southern reaction to the abolitionist Movement grew so violent that Local people who opposed slavery Went underground or moved north.

Calhoun, his health now failing, was shaken by the Wilmot Proviso and its naked effort to limit the extension of slavery. But he was well enough to enunciate the Southern view when, with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, Mexico ceded to the United States an immense domain of nearly one million square miles, including all the territory between Texas and the Pacific. Calhoun argued that the territories were not federal property but the joint possession of the individual states, and that Congress therefore had no authority to intervene on the question of slavery. And since slaves were no more than chattel, the Southerners should be as free to transport them to new territories, as others were to move with their mules and oxen. He declared: "I am a Southern man and a slaveholder. I say, for one, I would rather meet any extremity upon earth than give up one inch of our equality-on inch of what belongs to us as members of this great republic!"

The controversy hung like a black cloud over Congress. In both houses, routine was often shattered by invective and threats of disunion. Calhoun warned his sectional rivals, "The North must give way, or there will be a rupture." Congressman Robert Toombs of Georgia, a large-hearted bull of a man, proclaimed his attachment to the Union but then warned, "I do not hesitate to avow before this House and the country, and in the presence of the living God, that if by your legislation you seek to drive us from the territories of California and New Mexico and to abolish slavery in this District, thereby attempting to fix a national degradation upon half states of this Confederacy, I am for disunion."

Northerners in Congress answered quickly in kind Senator Salmon P. Chase of Ohio declared, "No menace of disunion will move us from the path which in our judgment it is due to ourselves and the people whom we represent to pursue." Congressman John P. Hale of New Hampshire refused to consider any further compromise. He cried, "If this Union, with all its advantages, has no other cement than the blood of human slavery, let it perish!"

Disfigures the palm of Captain Jonathan Walker. The mariner, Arrested in 1844 while trying to Smuggle seven slaves from Florida to Liberty in the West Indies, was held in Solitary confinement for a year.

In the meantime, the issue of the extension of slavery caught the eye of recently elected President Zachary Taylor, the hero of the Mexican War. Taylor was a Louisianan and a slave owner, but he was first and foremost an old general who wanted to serve his country. And with a soldier's naive disregard for political protocol, he sought and found a simple solution to the problem.

In 1849, California and New Mexico were still being administered by military officers. Neither had been authored to organize a territorial government, under whose aegis each region would prepare or statehood. It was during this fledgling stage before statehood that the issue of slavery was most volatile; because a territory was still a ward of the federal government, the U.S. Congress could meddle in any decision made by the territorial government.

As it happened, California, thanks to the gold rush, already had far more than the 66,000 people required for statehood. Since every established state had an unchallenged right to decide for itself the status of slavery, Taylor decided to get California, and later New Mexico, to apply for statehood without going through the territorial phase thus removing the federal government from the troublesome slavery decision.

Taylor sent agents to California and New Mexico to persuade the settlers there to make application for statehood. California, very much need of civil government to establish order in the unruly gold camps, complied gladly with the President's proposal. By November of 1849 a constitution had been drawn up and California had opted to enter the Union as a free state. New Mexico made a start on a similar procedure.

When the proslavery Southerners woke up to Taylor's maneuverings, they could scarcely believe what was taking place. They saw a betrayal by one of their own, a President whom they had expected to protect their sectional interests. They accused Taylor of pressuring California into applying for statehood before the citizens really wanted it. They voiced a suspicion that the President was conspiring with Northern zealots to deny the South any rights in the new territories. They threatened secession. Northerners tried to pacify them with the argument that the Mexican lands were unfavorable for slavery anyway; But Alexander H. Stephens of Georgia retorted that a principle was involved. "Principles, sir, are not only outposts, but the bulwarks of all Constitutional liberty; and if these be yielded, or taken by superior force, the citadel will soon follow."

All the angry Southern voices only provoked familiar rhetoric from the Northerners. "The North is determined that slavery shall not pollute the soil of lands now free, even if it should come to a dissolution of the Union," an Ohio newspaper proclaimed. Slavery, said Senator William Upham of Vermont, was "a crime against humanity, and a sore evil in the body politic."

It seemed that the country would surely break apart. From Mississippi came a summons to states to meet in Nashville in June 1850 to ' aw up a plan for dealing with the "gross injustice" of the North. But then men of moderation on both sides turned for a solution to Henry Clay, the so-called Great Pacificator. Clay was aged and ailing, but his stature and oratory still could sway intransigent partisans.

In January of 1850, Clay presented his solution to the gravest crisis of the half-century. He proposed that California should be allowed to enter the Union as a free state, just as it wished, but that Congress should refrain from intervening in the slavery question in any other new territories carved from the Mexican cession. Clay also offered resolutions on three side issues that had cropped up during the debate: that Texas be compensated for yielding certain western tracts to New Mexico, that the sale of slaves be abolished in the District of Columbia, and that Congress enact stiff new laws to assist slave owners in the capture and return of runaway slaves.

Clay defended his compromise plan in a series of speeches in the senate; for each ad-dress, the gallery was packed with citizens who sensed that the occasion would be Clay'~ swan song. The old Kentuckian was nothing less than magnificent. In his rich voice called for reason. He urged Southerners not to complain if the state of California rejected slavery. And he demanded of Northerners: "What do you want, you who reside in the free states? Have you not your desire in California? And in all human probability you will have it in New Mexico also. What more do you want? You have got what is worth more than a thousand Wilmot Provisos." Clay pointed out that Northerners had nature on their side and facts on their side-that the territories in question had no slavery and were unsuited to slavery. He ended by warning Southern extremists that secession would mean nothing less than war, and he begged them "to pause at the edge of the precipice, before the fearful and disastrous leap is taken into the yawning abyss below."

Clay's plea for moderation was countered on March 4 by John Calhoun, now dying of tuberculosis. (He had less than a month to live.) He was so weak that a colleague had to read his speech. In it Calhoun never mentioned Clay or the compromise measures; instead, he called on the North, as the stronger section of the country, to make concessions to preserve the Union. The North, he said, should grant slave-owners equal rights in the territories of the new West, quiet the abolitionist agitation against slavery and guarantee the return of fugitive slaves. Barring those concessions, Calhoun proposed that the North and the South separate and each section govern itself in peace. If that were not possible, he warned the North, "We shall know what to do, when you reduce the question to submission or resistance."

Calhoun's challenge was met by the magisterial Daniel Webster, in what was perhaps His finest speech. He began, "I wish to speak not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a Northern man, but as an American, and a member of the Senate of the United States. I speak today for the preservation of the Union. Hear me for my cause." Webster implored the Northern radicals to soften their position. The Wilmot Proviso, that "taunt or reproach" to-the South, was unnecessary because conditions in the West were unfavorable to slavery. "I would not take pains to reaffirm an ordinance of nature," he stated, ''nor to reenact the will of God.

Webster's speech was considered a betrayal by the abolitionists, but its message of moderation received high praise elsewhere. Even the fiery Charleston Mercury lauded his effort: "With such a spirit as Mr. Webster has shown, it no longer seems impossible to bring this sectional contest to a close." Under the able direction of Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, Clay's proposals ran the legislative gantlet and were enacted into law by September.

Clay's Compromise of 1850 was hailed as the Union's salvation. A schism had been averted, and Americans, now breathing a bit more easily, looked ahead hopefully to a future free of sectional rancor. Indeed, the compromise strengthened the Southern moderates and thereby helped thwart the plans of belligerent Southern agitators to forge a bloc of separatist Southern states.

But - far from curing the nation's ills, the compromise contained a minor measure that would do major damage to the chances for a lasting settlement. That measure was the Fugitive Slave Law.

Runaway slaves were not a serious problem for planters; not many more than a thousand escaped each year, even with the help of the Underground Railroad, and relatively few of them were able to reach sanctuary in the North. Even so, the Fugitive Slave Law was designed to mollify the South, and it did so with some of the harshest national regulations yet instituted by Congress. It placed the full power of the federal government behind efforts to recapture escaped slaves. It created federal police power: A cadre of U.S. commissioners was authorized to issue warrants for the arrest and return of runaways. And it empowered the commissioners to dragoon citizens into slave-catching posses. The intervention of the federal government in the plight of escaped slaves infuriated even moderate Northerners. Ralph Waldo Emerson called the fugitive measure a "filthy law," and many Northerners vowed to resist it. Not even the U.S. Army could enforce the law, predicted Ohio Congressman Joshua Giddings: "Let the President drench our land of freedom in blood; but he will never make us obey that law."

Once the Fugitive Slave Law was on the books, it was no longer enough for a runaway to reach the North. Professional slave hunters, armed with affidavits from Southern courts, scoured Northern cities, not only ferreting out runaways but sometimes kidnapping free blacks, of whom almost 200,000 lived in Northern communities. Runaways who had felt secure in New York and Philadelphia and Boston were frightened enough to take flight across the Canadian border.

Others fought back. Blacks and whites in Northern cities formed vigilance committees to protect fugitives from the slave catchers. Boston was virtually in a state of insurrection, with abolitionist mobs roaming the streets and influential abolitionist clergymen advocating civil disobedience to the slave-catching municipal police. A Boston slave couple named William and Ellen Craft were whisked from the reach of a Georgia lawman who had come to get them. Fred Wilkins, a black waiter who was being held in a federal courthouse in Boston, was spirited away by a crowd of blacks who burst through the doors of the courthouse.

Then came the wrenching case of Anthony Burns, a Virginia escapee who had been working in a Boston clothing store. When Burns was arrested by a federal marshal, abolitionists held a mass meeting at Faneuil Hall and were whipped into action by fiery oratory. "I want that man set free in the streets of Boston," shouted Wendell Phillips, the well-born reform lecturer. "If that man leaves the city of Boston, Massachusetts is a conquered state."

The crowd stormed the federal courthouse where Burns was being held. In the melee a special deputy was killed, and the federal marshals and deputies were hard put to restrain the mob. Finally, the federal government sent in Regular Army troops to take Burns out. With flags flying at half-mast and bells tolling a dirge, Burns was marched through crepe-hung streets to the harbor and put aboard a Virginia-bound ship.

"When it was all over," a Boston attorney wrote, "and I was left alone in my office, I put my face in my hands and wept. I could do nothing less." Countless Northerners were galvanized by Bur ' fate. "We went td bed one night old fashioned, conservative, Compromise Union Whigs," wrote one, "and waked up stark mad abolitionists." Popular outrage stirred the North to legal action. Nine states passed personal-liberty laws designed to frustrate the Fugitive Slave Law and protect blacks in their domain. Southern slave hunters found it so difficult to prove their case and to get cooperation from Northern authorities that most gave up the chase.

The plight of the runaways inspired and brought to publication in 1852 the ultimate piece of abolitionist propaganda. This work, a novel by a meek and pious New Englander named Harriet Beecher Stowe, was Uncle Tom's Cabin, or Life among the Lowly.

As literature the book suffered from a contrived plot and stereotyped characters.

Yet it personalized the evils of slavery, and the suffering of Uncle Tom and Eliza and Little Eva tugged at the heartstrings of readers who had been unmoved by abolitionist rhetoric. The book became a bestseller almost overnight; within a year 300,000 copies were sold, and the story reached an even wider audience in the form of a drama, which dozens of touring troupes performed in lyceums and in meeting halls all over the country. Meanwhile, Southern readers ground their teeth over Mrs. Stowe's claims that their society was evil; their rage and frustration strengthened the garrison mentality that had gripped the South.

So it was that the United States at mid-century stood in grave peril. Opposition to slavery had permeated and pervaded the North; few Northerners knew of or cared about the Southern planters' plight. In the South, the commitment to slavery was now inalterable. It did not matter that only about 350,000 people-one family out of four-actually owned slaves. Most Southern whites firmly believed that their livelihood, their dear institutions and traditions, and indeed their personal safety amid almost four million blacks all depended on preserving and extending the use of slave labor.

The meager chances for a rapprochement between the North and the South were further dimmed in 1852. Henry Clay and Daniel Webster followed John Calhoun to the grave, leaving their constituencies in the hands of less seasoned, less wise, less patient leaders. At the same time a new ingredient was added to the North-South quarrels-an ingredient that gave Americans everywhere a preview of their future. It was organized violence, and it erupted in Kansas.