By Jack Steed

The author of this story, a civil war collector, recently came across the effects of Captain Andrew Emery, Third United States Colored Cavalry. The artifacts are now owned by Guy Andrew Emery, Captain Emery’s Grandson. Included among the items was a rare book, written in 1908 by Mr. Ed Main, former Mayor, Third U.S.C.C. The book, in which official reports are coupled with specific detail of battle, makes for exciting reading. It also opens up to history the campaigns of a heretofore little honored regiment. In poring through the book, the author found Captain Emery’s name fairly leaping from the pages. Thus was born the inspiration for the true story, which follows.

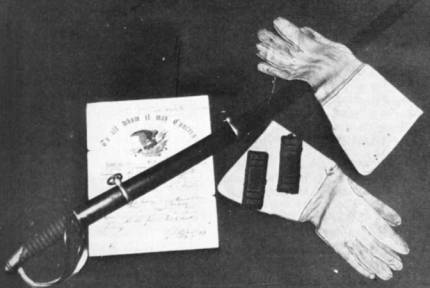

Author was struck with vicarious feelings of cavalry charges as he handled saber of Yank Emery. Other artifacts include: Gauntlets, Shoulder Straps, and Discharge paper. (All now owned by Guy Andrew Emery)

of the

3rd and 4th Illinois Cavalry

of the

3rd and 4th Illinois Cavalry

It is mid 1862, during one of the in numerable skirmishes between western elements of the Union and Confederate armies. Many of these encounters were unrecorded and, indeed, this one also must pass without written recall. To one participant, however, an incident occurred which gave him a name that was to last the remainder of his life.

Always in the forefront of battle, Andrew Emery found himself cut off from the remainder of his company by a sudden rebel rush. Surrender? Not Andrew Emery. He simply began attacking back toward friendly lines. "Shoot the Yank'." rang the shouts of the enemy and a hail of bullets swirled about Emery as he hastened for the safety of the Union position. Miraculously, he returned unscathed. The name given him that day by the Confederates stuck and from that day forward he became "Yank" Emery.

Andrew Emery was born in Maine, in 1833. He went west to Lockport, Illinois in 1855. In April 1861 he enlisted under President Lincoln's first call for troops. Re enlisting following the expiration of his three month duty term, Emery was assigned to company D, Fourth Illinois Cavalry. The instant bullets began to fly; Emery began to be noticed by his superiors. His bravery was particularly noticeable at both Fort Donelson and Shiloh (Pittsburgh Landing.) Following the latter battle Emery was promoted to First Duty Sergeant, for meritorious conduct in battle. He remained with the Fourth through all its subsequent maneuvers, campaigns and engagements leading to the fall of Vicksburg, July 4, 1863.

In September 1863, acting upon a suggestion by General Grant, one regiment of Colored cavalry was authorized to be raised and equipped at Vicksburg. The designation originally was to be: First Mississippi Cavalry, African Descent and this name does appear on some early communications. Very soon, however, the name was changed to: Third United Colored Cavalry. General Grant took much personal interest in the regiment and recommended for its Colonel, Major E.D. Osband. Up to this time Major Osband had been commander of General Grant's personal escort: Company A, Fourth Illinois Cavalry.

The North saw little reason that black men could not be trained to perform on a level with whites. The potential problem was one of leadership. In order to give the regiment every chance for success, it was decided to use as officers white men whose reaction to combat was already known.

The first and foremost requirement was of bravery shown in their old regiments. Next, their soldierly qualities were considered. Finally, the officer candidates underwent an exacting examination in military tactics administered by a board of army officers. Without these qualifications, influence mattered not at all. This rigorous selection process gave the black cavalrymen some of the finest officers ever put in command of Union Army troops. Among those brave enlisted men who received commissions in the newly formed Third United States Colored Cavalry, was the subject of this treatise, Andrew Emery

The intense bitterness of the times caused senseless hatreds to abound. Among these was the "Black Flag" which meant death to captured black Union soldiers and their white officers. It took men born of an iron will to offer themselves up to the

Threat. Undeterred Sergeant Emery of the Fourth now became Captain Emery of the Third, and Yank Emery embarked upon a heroic record of service.

The enlisted men of the Third were handpicked from thousands of available blacks. Those chosen had to be bright, young, active men of medium build, with riding experience preferred. As most blacks of the day were straight off the farm, they were natural horsemen. They quickly adapted to military discipline and proved quite proficient in all aspects of duty. Many had been associated with the army for many months prior to being selected to be soldiers. They had served the Union as servants, cooks, hostlers, teamsters and pioneers. Many were familiar with the hardships of war and were, in every sense of the words old campaigners without bearing arms. The opportunity to fight for the North was eagerly accepted by these men. This combination of tough officers and determined cavalrymen made for a formidable mounted force.

Beginning October 9, 1863 the Third was in nearly constant contact with enemy forces for the remaining eighteen months of the war. Before long, both friend and foe alike knew that the black regiment meant business. Most of this contact was in the form of raids, or expeditions as they were called. Using Vicksburg as their base they raided into Louisiana, Arkansas, Tennessee and Mississippi; tearing up track, burning bridges, capturing supplies, and engaging the enemy wherever he could be found. These sorties were conducted on a continual basis, rendering no enemy strong point safe from their sudden appearance. From the Pearl River to the Yazoo, from Jackson to Woodville, they harassed and disrupted Confederate forces in the area. Relocating at Memphis early in 1865, the raiders moved down the Mississippi in April, May and June. Though greatly resented by area residents, the unit maintained strict military discipline concerning the rights of private southern citizens. Their conduct was impeccable in this regard.

The end of the war found the Third in possession of a record any regiment would have been proud of: Though occasionally being forced back by opposing troops, the Third had never once broken in the face of the enemy, and never ended up losing any battle. No enemy of like numbers ever stopped their charge.

Captain Emery's contribution to the great record of the regiment was considerable, as we shall now see.

We find him in command of company B of the Third on the expedition of December 12, 1863. Two hundred enlisted men plus officers crossed the Mississippi into Louisiana on a scouting and recruiting mission. Reaching the Boeuf River they turned north, entering Arkansas. Toward evening, the command camped on the plantation of a Mr. Merriweather. Unknown to the troopers, Merriweather was able to contact Confederate authorities and apprise them of the Third's presence on his property. As the Union soldiers began to stir the following morning making coffee and cooking breakfast they were suddenly confronted by the Rebel Yell and a crash of shotgun blasts. Out of the woods surrounding the farm burst an enemy force nearly double their own. This force threatened to annihilate the command, right then and there.

Racing into the Merriweather yard, Emery was able to form his company behind the picket fence at the front of the house. His was the first unit to organize a resistance to the attackers. "Charge the fence!" shouted the enemy and a mad scramble followed for possession of it. Several horses which had been tied to the fence were killed when the enemy struck. These animal bodies provided cover for the men of B Company, who now began a desperate stand. One Rebel grasped the barrel of trooper Henry Wilson's carbine, attempting to wrest it from him. Wilson, later a black Chicago attorney, simply pulled the trigger, discharging the gun into the Rebel's chest and inflicting what must have been a fatal wound. The fighting at the fence reached the critical stage. For a time it seemed as though the Union force faced certain defeat, a defeat laced with ominous overtones for the men of the Third. At the most critical moment, when defeat seemed inevitable, Lieutenant Calais with company A crossed the road to the left, moved quickly through the woods and fell with a vengeance upon the enemy's right flank. This sudden reversal of fortune initiated an enemy rearward flight. Though one quarter of the Union force had been lost in the ambush, the remaining men of the Third hotly pursued the now retreating Confederates. The trail led to the river, but the enemy had crossed to safety by the time of the arrival of the Federals.

This victory, coming as it did in the face of near disaster, gave the troopers of the Third great confidence in themselves and marked one of the proudest days in the unit's history. They literally snatched victory from the jaws of defeat. Word of the outcome of the Boeuf River fight soon made its way through the Mississippi Valley and gave the Third a big boost in morale and boosted the numbers of officers and men desiring to join the regiment.

On the expedition up the Yazoo River, January 31 to March 10, 1864 the combined forces of the Third, the Eleventh Illinois Infantry, and the Eighth Louisiana Colored Infantry, some 1,200 men in all, fought several continuing engagements with the enemy before fighting a frantic battle for survival at Yazoo City. There, the command was besiege by nearly 5,000 men under Confederate generals Ross and Richardson.

The stillness of morning on March 5, 1864 was broken by the reports of the carbines of "B" Company, on picket a mile outside town. As volley after volley sounded, the main Union force at the city was alerted and put in readiness. The strong enemy attack forced "B" Company back to the breastworks of Yazoo City where, after a hard day long fight, a successful defense was made. Unable to breach the Federal line, the Confederates ultimately broke off the assault and withdrew from the vicinity.

On the expedition to Jackson and the Pearl River, July 2 through 10, 1864, B Company was again attacked while on picket duty at the most advanced position of the command. Hastening to the aid of Emery, Major Cook found him "gallantly holding his ground." The expeditions go on. First, the Grand Gulf in mid summer of 1864, then to Natchez, Fort Adams and Woodville early in the fall.

On November 27, 1864 there occurred an Operation destined to rank as the single most notable achievement ever accomplished by the Third. The ramifications of this expedition were felt all the way to Nashville, where Union General Thomas was preparing to attack Confederate General Hood, who was menacing Tennessee. Hood received his reinforcements by way of a railroad, which bridged the Big Black River near Vaughn Station, Mississippi. Twice before, Union forces had launched unsuccessful assaults on this bridge.

Situated in almost impenetrable swamp, the span was protected by a Confederate force housed in stockades on both sides of the river. A contingent of the Third, under Major Cook, was selected to make a new attempt to destroy the bridge. The importance of this assignment indicated the high level of esteem to which the regiment had risen.

The companies of Major Main and Captain Emery were sent quietly ahead, through the swamp below the railroad bedding. Cook then marched along the railroad with the remaining men of the command. The purpose was to deceive the enemy with a demonstration in front, while Main and Emery drew into a favorable flanking position. The journey through the swamp was lengthy and tedious, the mire being waist deep in areas. Nevertheless, as Cook's men advanced above, the groups of Main and Emery crept closer below. Finally all was in readiness...

Cook now showed himself, alternately closing and retreating, in an attempt to lure the enemy outside his fortifications. Mesmerized by Cook's men, who remained just beyond an effective musket range, the Confederates poured out of the forts in order to gain a better angle of fire. At the pre arranged signal, a bugle blast, Main's and Emery's men opened a withering oblique fire into the rebel troops. Caught in the trap, the shattered defenders milled about in disorder, then retreated towards their stockades. While Main's and Emery 5 men sent an unceasing carbine fire into the enemy, Cook and his men swarmed toward the forts. The near fort fell quickly; the fort across the river required a maximum assaulting effort. Several men were shot from the bridge as they attacked across the railroad ties. Many more succeeded in crossing and these men now fell on the remaining redoubt. Pouring through the sally ports, they engaged the enemy in hand to hand combat. The remaining Rebels were forced from the stockade and retreated into the swamp. Ignoring the scattered musketry from the swamp, the troopers of the Third poured coal oil over the bridge, piled brush upon it, and fired the bridge; remaining until it was utterly destroyed. The Federals then tore up track for a mile in each direction. This greatly impeded the re supplying of Hood who, on December 15-16, was totally crushed as Thomas came out of Nashville and sent Hood reeling into Mississippi. In General Order #81, Major General E.R.S. Canby, commanding the military division of West Mississippi, called the destruction of the bridge "one of the most daring and heroic acts of the war. "This is the same General Canby who was assassinated by Captain Jack, April 11,1873 during problems with the Modoc Indians.

Captain Emery played an important role during Grierson's raid from Memphis to Vicksburg, early in 1865. At Franklin, Mississippi, a small hamlet situated between West Station and Benton on the Franklin turnpike, Rebels in large numbers lay in woods waiting to ambush the approaching Federals. Though the enemy position was well chosen, they had not counted on the battle tested abilities of the Union force at their front the Third. Noting the enemy position, Colonel Osband directed Emery to lead eight companies on a flank attack while the main force continued along the road they had been traveling. Emery's attack through the woods took the enemy by complete surprise. The Rebels fought back bravely, however, and succeeded in charging the mounted men at their front, under Major Main. Main retreated under threat of being cut off. A detachment of the Fourth Illinois Cavalry, under Captain Merriman, came to the aid of Main. The combination of Emery's dismounted attack from the flank and the counter attacking Illinois cavalry at the front finally broke the enemy's spirit and he withdrew, unwilling to renew the fight.

The arrival of units of Grierson's command in Vicksburg, January 5, 1865 initiated a day of rejoicing for the Union soldiers occupying the former Confederate citadel. The raid showed the people living in the area the power of the federal forces stationed there. Millions of dollars of rebel property had been destroyed, many miles of track uprooted, supplies captured in abundance and over one thousand prisoners taken.

Into early 1865, the Third made continuous raids. April found them commencing the final expedition of the war. Lee had surrendered in Virginia; federal forces held Richmond and Confederate President Davis was in flight. It was rumored he might attempt to escape to Texas. On April 27, General George Thomas in Nashville ordered all Union cavalry forces alerted to intercept him, if possible. General N.J.T. Dana, commanding at Vicksburg, consequently ordered Colonel Osband to leave Memphis and take the Third down the Mississippi on a searching mission. On May 16, Colonel Osband took leave to assume his new duty as post commander of Jackson. The command of the expedition was transferred to Major Main. To this point, no enemy soldiers had been seen. Not long after Osband left, a skirmish took place after dark. Next morning a pair of saddlebags were found. Inside was a Confederate general's coat and a pair of spurs. The spurs were marked: J.B. Hood. Being in the vicinity of Woodville, and thinking the Confederate commander might be in the village, a rapid raid was made on Woodville. Yank Emery led the advance. Close outside town some enemy soldiers were seen. With sabers drawn, the Third charged the enemy from front and flank. The enemy fled perceptibly. Not long after entering Woodville, a group of citizens informed Main that, as General Johnston had already surrendered to General Sherman, Main's attack outside town was unjustified. Main replied that his duty required him to repel all enemies of the United States whenever resistance was shown.

A humorous incident happened during the charge on Woodville. It provided the men with many pleasant moments as they retold it time and again. Aboard a gunboat the night before the Woodville attack, a naval officer became friendly with Captain Emery. Next morning, the sailor was given permission to accompany the regiment on the charge into town. He was given a tried and true cavalry mount. As he rode alongside Emery down the main street, the bumpy terrain caused the navy man to bounce out of the saddle, sending him sprawling into the dust. As no enemy troops were found in Woodville, Emery returned to offer aid to the fallen hero, whose most serious injury proved to be his pride. The sailor took the resulting ribbing graciously, but never again requested to join the cavalry.

The war having ended, the regiment was mustered out early in 1866. The men then went their separate ways. Brevet Brigadier General Osband lived only a few more months, dying in a cholera epidemic. Major Main lived in the South a long while, and then moved to Wagoner, Oklahoma. One officer of the Third, Lieutenant Edwin Farley, eventually became Treasurer of Kentucky. Yank Emery went back to his hometown of Lockport and entered the confectionary business. His candy enterprise prospered and he traveled extensively throughout America. His wartime experiences coupled with his extreme joviality enabled him to become a very popular public speaker throughout Will County. Often, black former soldiers who served with him came to his Lockport home to visit their old Captain. These men were always greeted enthusiastically and, inevitably, stayed for dinner and reminiscing. Emery died of natural causes in 1911 and is buried in Lockport.

Andrew Emery's story is typical of countless peace loving Americans who, when the situation demands, rise, en masse, to answer their country's call. These men may be white, black, brown, or shades in between. They may come from any geographic locale. In the heat of battle they fight as men possessed. Peace sends them back to their former pursuits occupations normally unrelated to their military training. It is an amazing and quite necessary national phenomenon. The Yank Emery’s of America have made us great and kept us free. Appreciation of their efforts is never out of date and they ought never be forgotten.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Third United States Colored Cavalry

Globe Printing Louisville, 1908

in his later years

with grandson

Guy