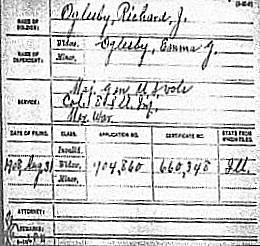

Richard J. Oglesby Company "C" and "I"

4th Illinois Volunteer Cavalry

Richard J. Oglesby, Republican from Macon County was next on Jan 16, 1865. He was born in Floysburg, Oldham, KY on July 25, 1824. He was orphaned at a young age and raised by his Uncle in Decatur, Macon, IL. He received only limited schooling and worked as a farmer, rope maker and carpenter. He was admitted to the Bar in 1845 and began the practice of law in Sullivan, Moultrie, IL. He served for two years in the Mexican War as 1st Lt. in Co C, 4th Illinois Regiment. He then spent two years mining in California then returned to Decatur and practiced law there. He was elected to the State Senate in 1860 and served for one session before resigning to serve in the Civil War. He served in the Union Army as Colonel, Brigadier General and Major General of the Eight Reg., Illinois Volunteer Infantry. He served as Governor of Illinois from 1865-1869 and then was re-elected in 1872 and served from Jan 13, 1873 to Jan 23, 1873 when he resigned to serve in the U.S. Senate for which he was also elected. He served there from Mar 4, 1873 to Mar 3, 1879. He declined to run for the Senate again and was elected Governor again to serve from 1885 to 1889. He retired to his farm, "Oglehurst" in Elkhart, Illinois. He died there Apr 24, 1899 and is buried in Elkhart Cemetery. He married Emma Gillette Keys and they were the parents of John Gillett Oglesby, born Mar 19, 1873, Decatur, and Macon, IL. John was Lt. Gov. 1909-1913 and again 1917-1921. John died May 26, 1938.

You will find Richard J. Oglesby in:

Context of United States Army Historical Register, 1789-1903, Volume 2

Alphabetical List of Officers of the Regular army (From It's Organization, September 29, 1789, to 1903) Who Were Killed or Wounded in Action or Taken Prisoner, With Date and Place.

Page 63.

Oglesby, Richard J., Company "I", 4th Illinois Cavalry

Books

History of Early Chicago

Modern Chicago and its Settlement

Early Chicago, and the Northwest by: Albert D. Hager

Page 217

American Civil War Battle Summaries

FORT DONELSON, TENNESSEE

FEBRUARY 14TH AND 16TH, 1862

Fort Donelson, Tenn., Feb. 14-16, 1862. U. S. Troops under Gen. U. S. Grant, and Commodore Foote's Gunboats. Fort Donelson was located on the left bank of the Cumberland River, about a mile and a half below the little town of Dover, and was built about the same time as Fort Henry (q. v.). It was a bastioned earthwork, on a bluff about 100 feet above the water and commanded the river for several miles down stream. On either side of this bluff streams flowed into the Cumberland, Hickman creek on the lower side and Indian creek on the upper, and along the ridge below Indian creek ran the road to Wynn's ferry. On the lower side of the fort two water-batteries had

been set in the side of the bluff about 30 feet above the water. The lower battery had nine 32-pounder guns and a 10-inch columbiad, and the upper mounted a rifled gun carrying a 128 pound conical shot and two 32-pounder carronades, while the armament of the fort proper consisted of 8 guns of heavy caliber. In the rear of the fort a line of rifle pits extended from Hickman creek to below the town of Dover, and along this line were 8 field batteries, numbering probably 40 guns.

After the fall of Fort Henry on Feb. 6, Grant prepared to move at once on Fort Donelson. But the rivers were rising, the road for 2 miles was under water, and the troops were kept busy in saving the camp equipage, etc., from the flood. A detachment of cavalry, however, went to the fort on the 7th, and skirmished awhile with the pickets and outlying works, merely to develop the enemy's strength and position. Knowing that the fort would be speedily reinforced as soon as the news of the surrender of Fort Henry reached Confederate headquarters, Grant at first contemplated making the attack with infantry and cavalry alone, but after the delay caused by the high waters he concluded to wait for the arrival of the gunboats, which had left Fort Henry immediately after the

surrender, to move down the Tennessee and Mississippi and ascend the Cumberland to assist in the assault on Fort Donelson. Foote left Cairo on the 11th with the 4 ironclads, St. Louis, Carondelet, Louisville and Pittsburg, and the two wooden gunboats, Tyler and Conestoga, expecting to form a junction with Grant on the 13th at the farthest.

In the meantime Halleck was busily engaged in forwarding supplies and reinforcements to Grant, so that when the attack was made the Union army numbered about 27,000 men, 5,000 of whom were engaged in guarding trains. The organization was as follows: 1st division, Brig.-Gen. John A. McClernand, consisting of the brigades of Richard J. Oglesby, W. H. L. Wallace and William R. Morrison and four batteries, 2nd division, Brig-Gen. Charles E. Smith, consisting of the brigades of John McArthur, John Cook, Jacob G. Lauman and George F. McGinnis, and three batteries; 3rd divisions Brig. Gen. Lewis Wallace, consisting of the brigades of Charles Cruft and John M. Thayer, with two batteries. In Wallace's division the 2nd and 3rd brigades were united under the command of Thayer. All the brigade commanders held the rank of colonel, though they subsequently attained higher rank. The confederates had also been heavily reinforced during the time Grant was waiting for the waters to subside and for the arrival of the fleet. In addition to the original garrison and the 3,000 men that went with Heiman from Fort Henry on the 6th, Bushrod Johnson arrived with about 6,000 on the 8th, Pillow came down from Clarksville on the 9th with 2,000 more; Brown's brigade came in about the same time; Floyd and Buckner arrived from Russellville with 8,000 on the 11th and 12th and Polk sent about 1,800 from Columbus. On the morning of the 13th the Confederate strength numbered not far from 20,000 men, and was divided into the following commands: Buckner's

division, including the brigades of Cols. W. E. Baldwin and J. C. Brown Johnson's left wing, consisting of the brigades of Cols. A. Heiman, T. J. Davidson and John Drake; Floyd's division consisting of the brigades of Cols. G. C. Wharton and John McCausland; the regular garrison, embracing the 30th, 49th and 50th Tenn. and commanded by Col. J. W. Head, and Forrest's cavalry.

On the morning of the 12th Grant left Lew Wallace with about 2,500 men at Fort Henry and moved with 15,OOO by two roads toward Fort Donelson. McClernand's division, preceded by cavalry, had the advance on both roads. About noon the head of the column commenced skirmishing with the enemy's pickets, the rest of the day being passed in feeling the Confederate position and in learning the nature of the ground, which was full of ravines and ridges and thickly wooded. By nightfall Smith's division was in front of Buckner's next to Hickman creek, while McClernand had crossed Indian creek and taken position on the Wynn's ferry road. All of the 13th was spent in maneuvering for position and making demonstrations to draw the fire of the enemy's batteries, with a view of

locating the weak points in the line of defenses. The Carondelet arrived that morning and fired a few shots at long

range, disabling one of the 32-pounders in the lower battery, but a shot from the rifled gun in the upper battery entered a porthole in the vessel, damaging her machinery and causing her to withdraw out of range. Toward evening the fleet arrived, bringing transports laden with reinforcements and, what was more welcome, supplies, as the men had left Fort Henry in light marching order with but one day's rations in their haversacks. Wallace, who had been ordered up from Fort Henry, arrived on the 14th and was assigned to a position between Smith and McClernand most of the reinforcements being added to his division, Skirmishers exchanged shots at intervals during the day and from time to time the gunners in the batteries fired a few rounds to try the range of the guns.

At 3 p.m. the 4 ironclad gunboats took position under fire and steamed slowly up the river firing as they came. When within less than 400 yards of the fort a solid shot plowed its way through the wheelhouse of the St. Louis, and almost at the same instant the tiller ropes of the Louisville were cut away. The two boats became unmanageable and drifted down the river, greeted by the exultant yells of the Confederate gunners. The Pittsburg and Carondelet covered the disabled boats as well as possible and the whole fleet fell back beyond the range of the guns that had wrought the disaster. This repulse of the gunboats made it plain that the fort, if it was taken at all, must be taken by the land forces, and preparations were at once commenced for an attack on the following morning. Other transports had arrived during the day with additional troops, which were assigned to positions in the line; McArthur was ordered to the right to support Oglesby, as it was feared the enemy might attempt to cut his way out at that point; batteries were brought up and placed in the most advantageous

positions, rations and ammunition were issued to the men, and when night came the men bivouacked without fires, resting on their arms so as to begin the assault as soon as the command might be given.

Buckner says it was decided at a council on the morning of the 14th to cut a way out that day and that preparations were made for such a movement, but the order was countermanded by Floyd. That night another council was held, at which it was agreed to make a sortie at daybreak on the 15th, and if it was successful to retreat to Charlotte by the Wynn's ferry road. Pillow was to begin the attack on McClernand's right. And this was to be followed by Buckner in an assault on the center of the division, driving it back on Lew Wallace and opening the way to the road, after which Buckner was to cover the retreat. Accordingly at 6 a.m. Baldwin's brigade moved out and was soon engaged with Oglesby. McArthur hurried up and formed his command on Oglesby's right, gradually widening the distance between his regiments and prolonging his right into a skirmish line. Oglesby moved the 18th Ill. to the right to strengthen the line and brought up Schwartz, battery, which opened a destructive fire on the enemy's advancing column. Pillow sent the 20th Miss. to Baldwin's support, but it was quickly forced to retire behind a ridge for shelter. Johnson's brigade next moved forward through a depression in the ground and succeeded in turning McClernand's right. McClernand sent to Lew Wallace for assistance and Cruft's brigade was ordered to the right, where it managed to check the enemy and for a time held its position. Deeming that the time had come for him to act, Buckner advanced a part of his division against W. H. L. Wallace's brigade. McClernand sent Taylor's and McAllister's batteries to Wallace's support and Buckner failed to break the line, his troops retiring before the destructive fire of the artillery. Fresh regiments were now hurled against Oglesby, whose ammunition was exhausted, and his men began to fall back. The enemy swept around his flank and appeared in the rear, isolating Cruft's brigade, which also retired. One regiment of Oglesby's command-the 31st Ill., commanded by Col. John A. Logan-held on after the others retreated and continued the fight until every cartridge box was empty. Logan was wounded in the thigh, but still kept his post. When his regiment was finally compelled to fall back for want of ammunition he had his wound dressed and again went to the front. As the 31st retired the 11th Ill., under Lieut -Col. Ransom, wheeled into the position and held it until charged by Forrest's cavalry, when it, too, retreated.

Up to this point the sortie had been successful. Pillow had opened the way for the Confederates to escape, but the escape was not made. This was due to Pillow's erroneous notion of the victory he had won. When he saw the broken ranks of the Union right wing falling back in confusion before him he believed Grant's entire army was in full retreat, and so telegraphed to Johnston. Buckner was in position to protect the withdrawal of the troops, but Pillow ordered him to move out on a road running up a gorge toward Lew Wallace's position in pursuit of the flying Federals. Buckner protested against such a move, suggesting that the objects of the sortie had been gained, and that the proper thing to do was to evacuate the fort at once. Pillow, however, was flushed with success and allowed his vanity to get the better of his judgment. He would listen to no remonstrance and again ordered Buckner to take up the pursuit. About the time that Buckner started up the gorge road an officer rode back past

Lew Wallace shouting: "All's lost! Save yourselves!" Instead of joining the retreating troops Wallace ordered Thayer's brigade forward to meet the enemy. Thayer moved his command at the double-quick up the ridge, formed a new line of battle at right angles to the old one, and behind this line McClernand's brigades rallied and refilled their cartridge boxes. Wood's battery was brought up and placed where it could sweep the road. These preparations were barely completed when the Confederates came swarming up the road and through the woods on both sides of it. The battery and the 1st Neb., commanded by Lieut. -Col. McCord, were the principal points of the attack. In his report Wallace says: "They met the storm, no man flinching, and their fire was terrible. To say that they did well is not enough. Their conduct was splendid. They alone repelled the charge. * * * That was the

last sally from Fort Donelson."

In the meantime C. F. Smith on the left had not been idle. With this command were Birge's sharpshooters, armed

with long-range Henry-rifles, and every man a skilled marksman. All day on the 14th this band of intrepid Missourians kept up from behind rocks and trees a continual fire, making it unsafe for a Confederate to show his head above the works. On the morning of the 15th Grant went to the flagship to hold an interview with Foote, who had been wounded during the action of the gunboats, and knew nothing of Pillow's sortie until about 1 p.m. He ordered C. F. Smith to storm the works in his front and then rode over to the right to take steps to recover the lost ground. Lew Wallace placed M. L. Smith's brigade, consisting of the 11th Ind. and 8th Mo., in the advance; Cruft's brigade in the second line, Morrison's brigade-the 17th and 48th Ill.-and the 46th, 57th and 58th Ill. in support. At 2 o'clock C. F. Smith led Lauman's brigade through the gates in the best order possible, reformed his line and charged up the slope. The Confederates in the rifle-pits fled precipitately, the four

regiments of the brigade, the 25th Ind., the 2nd, 7th and I4th Iowa, rushed in and planted the national colors over the works. This occurred while Buckner was engaged in trying to carry out Pillow's order to pursue the retreating Federals. Later he came back and vainly tried to dislodge Smith, but the latter was there to stay.

When Lew Wallace heard the sound of Smith's attack he ordered his line to advance against the ridge held by Drake's brigade and the 20th Miss. The 11th Ind. had been drilled in Zouave tactics, which now came in good play. Falling to the ground when the enemy's fire was hottest, then springing to their feet and running forward when it slackened, all the time keeping up a well directed fire, they gradually forced the Confederates back toward their works on the summit of the ridge. When near the ridge the Unionists commenced loading and firing as they advanced. Unused to this style of warfare the enemy gave way. The supporting column hurried up at this juncture, pressed the advantage gained and drove the Confederates within their works. The road to Charlotte was closed and the opportunity to escape had passed.

That night the Confederate generals held another council of war. The session was somewhat stormy, the criminations and recriminations between Buckner and Pillow growing at times especially bitter. Scouts were sent out to ascertain the position of the Federals and came back with the information that the Union lines occupied the same position as before the sortie. Some of the generals doubted the correctness of this statement and other scouts were sent out who came back with the report that every foot of ground from which the Federals had been driven in the morning had been reoccupied. Pillow still clung to the notion that they could cut their way out.

After canvassing the situation in all of its aspects the command was turned over to Buckner, who immediately announced his determination to surrender the fort. Floyd and Pillow declared they would never surrender, and Buckner agreed to their cutting their way out, or escaping as they could, provided it was done before an agreement was reached with the Federal commander as to the terms of capitulation. Pillow started out to make arrangements for his escape, at the same time giving Forrest directions to cut his way out. Calling his command together about 3 o'clock on Sunday morning of the 16th, Forrest went up the river road through the backwater,

which in places came up to the saddle-skirts, and reached Nashville the following Tuesday. About 200 of his men refused to go and were surrendered. Pillow and his staff crossed the river in a small flatboat and walked to Clarksville. About daylight two steamboats, which had, been sent up the river with prisoners and wounded Confederates, returned to the fort. Floyd took possession of the boats, embarked four Virginia regiments and steamed off up the river, leaving the 20th Miss. of his brigade behind.

Shortly after daybreak the notes of a bugle were heard in the direction of the fort, announcing the approach of an officer with a communication from Buckner, asking for an armistice until noon and the appointment of commissioners to agree on the terms of capitulation. Then it was that Grant sent his famous message, viz: "No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works." Having no alternative Buckner was forced to comply, and the Union forces marched in and took possession. The Union loss at Fort Donelson was 500 killed, 2,108 wounded and 224 missing. No accurate report of the Confederate casualties was made. Floyd estimated it at "about 1,500;" Pillow thought it was "about 2,000," and the Confederate Military History places it at "about 1,420." The same is true of the total strength of the

Confederate army and the number of prisoners surrendered. McClernand, in his report, says: "Our trophies corresponded with the magnitude of the victory; 13,300 prisoners, 20,000 stands of small arms, 60 pieces of cannon, and corresponding proportions of animals, wagons, ordnance, commissary and quartermaster's stores fell into our hands." But the most important result of the fall of Fort Donelson was the opening of the Cumberland River to the passage of the Union gunboats and transports and the breaking of Johnston's line of defense.

Source: The Union Army, vol. 5